Write a Program That Reads Data From Restratings

- Research article

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Reducing the use of physical restraints in dwelling house care: development and feasibility testing of a multicomponent plan to support the implementation of a guideline

BMC Elderliness volume 21, Commodity number:77 (2021) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

A validated testify-based guideline was adult to reduce concrete restraint utilize in home care. However, the implementation of guidelines in dwelling care is challenging. Therefore, this study aims to systematically develop and evaluate a multicomponent programme for the implementation of the guideline for reducing the use of physical restraints in home intendance.

Methods

Intervention Mapping was used to develop a multicomponent program. This method contains half dozen steps. Each step comprises several tasks towards the design, implementation and evaluation of an intervention; which is theory and evidence informed, likewise as practical. To ensure that the multicomponent program would support the implementation of the guideline in home care, a feasibility study of eight months was organized in one main care district in Flanders, Belgium. A concurrent triangulation mixed methods design was used to evaluate the multicomponent program consisting of a knowledge test, focus groups and an online survey.

Results

The Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Planned Beliefs are the foundations of the multicomponent plan. Based on modeling, active learning, guided practice, conventionalities selection and resistance to social pressure, eight practical applications were developed to operationalize these methods. The key components of the program are: the ambassadors for restraint-free home care (n = 15), the tutorials, the physical restraint checklist and the flyer. The results of the feasibility study show the necessity to select uniform terminology and definition for physical restraints, to involve all stakeholders from the offset of the procedure, to take time for the implementation process, to select competent ambassadors and to interact with other home care providers.

Conclusions

The multicomponent program shows promising results. Prior to futurity use, further inquiry needs to focus on the terminal two steps of Intervention Mapping (plan implementation plan and developing an evaluation plan), to guide implementation on a larger calibration and to formally evaluate the effectiveness of the multicomponent program.

Background

Despite the harmful effects of restraint use on older persons, family caregivers and professional intendance providers, restraints are still frequently used in home intendance [i, 2]. A recent systematic review states that, depending on the definition used, the prevalence of restraint use in older persons in dwelling house care ranges from five to 24.vii% [3]. Until recently, no consistent definition of physical restraints could be found in the literature. A Delphi written report of Bleijlevens et al. (2016) developed an internationally accustomed definition: "Any action or procedure that prevents a person'south free body movement to a position of pick and/or normal access to his/her trunk by the use of whatsoever method, attached or next to a person'south body that he/she cannot control or remove easily" [iv].

Home care in Flemish region is delivered by various professional care providers such equally general practitioners (GPs), registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, home health aides, occupational therapists, and physiotherapists. Each professional person intendance provider has an essential function in providing care for people with a care demand. This role is in accordance with specific constabulary and regulations of medical and healthcare professions [five]. In Flanders the GPs have a central function in home intendance. GPs are often key persons in the development of an private intendance program, in close collaboration with specialists and other professional intendance providers. In the decision-making process for the use of restraints, family, breezy caregivers and professional care providers, mainly registered nurses, are involved [1, six,vii,eight,nine]. Co-ordinate to the electric current legislation, only doctors, registered nurses, certified nursing administration (if they meet certain conditions such as working in a structured squad and under direct supervision of a registered nurse) and informal caregivers (if they meet certain atmospheric condition such as training from a nurse or GP, informal caregiver certificate, …) can apply physical restraints when needed [five, 10, 11]. Yet, literature shows that, in exercise, GPs are less involved in the decision-making process and the application of restraints [three]. Also home wellness nurses in Flanders stated that GPs had no clear office in deciding whether to use restraints [1].

The influence of patient-, nurse- and context related factors make the controlling procedure for the use of restraints complex [12]. In particular, the prominent role of the informal caregiver is challenging. A qualitative study reveals that breezy caregivers accept a dominant role in the use of restraints. This can consequence in conflicting opinions of restraint utilise between professional person home intendance providers and informal caregivers [ane]. Informal caregivers are significantly less aware of the harmful effects of physical restraints (e.g. bruises, increased dependence, depression) and have a more positive perception of their use [1, 2, 13, 14]. Furthermore, a study concludes that the cognition of care providers on alternatives for restraint employ in home care is limited [6]. The occurrence of conflicting opinions, the lack of awareness of the harmful effects of concrete restraint use and limited noesis among older persons, breezy caregivers and professional care providers add to the complexity of the determination-making process in the domicile care setting and stress the need for a clear policy on restraint use in home care [1, 2]. Therefore, Scheepmans et al. (2016, 2020) developed the first validated evidence-based guideline that aims to increase sensation, noesis and competences to fairly deal with questions about restraint use in home care [fifteen, sixteen]. The Belgian Middle of Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBAM) evaluated, validated and approved the scientific quality and reliability of the guideline [17].

However, the development and dissemination of a clinical exercise guideline is non sufficient for its integration and routine use in daily practice [eighteen]. A systematic review shows that the rates for adherence to clinical guidelines vary from approximately 20 to 80%, with a median adherence of 34% [xix]. The implementation of guidelines in home care organizations entails a complex intervention [20]. Complex interventions, such as multicomponent programs, are interventions that consist of several interacting components, which need modify at multiple levels [18, 20,21,22]. Implementation of a circuitous intervention requires an exploration of the barriers and facilitators for guideline employ, likewise as awareness, agreement, adoption and adherence of the adopters during each step of the process [19, 21]. Testify from residential care settings suggests that using a multicomponent approach involving policy change, leadership and education tin reduce the use of physical restraints [23,24,25,26]. Yet, the implementation of guidelines is even more challenging in home care [20]. Home care differs from residential intendance every bit a result of its particular characteristics like interorganizational structures and squad compositions [20]. In habitation care, where professional person care providers enter briefly the personal environment of the older person, they merely see the patient for a short amount of time and cannot ensure 24-h coverage and supervision when a person is being restrained [three]. Thus, the specific characteristics of the domicile care setting brand it hard to translate existing evidence from acute and residential care to the abode care setting.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous research apropos the implementation of a guideline that aims to reduce physical restraints in habitation care. Therefore, the overall aim of this study is to systematically develop and evaluate a multicomponent program for the implementation of a guideline for reducing the use of physical restraints in home care.

Methods

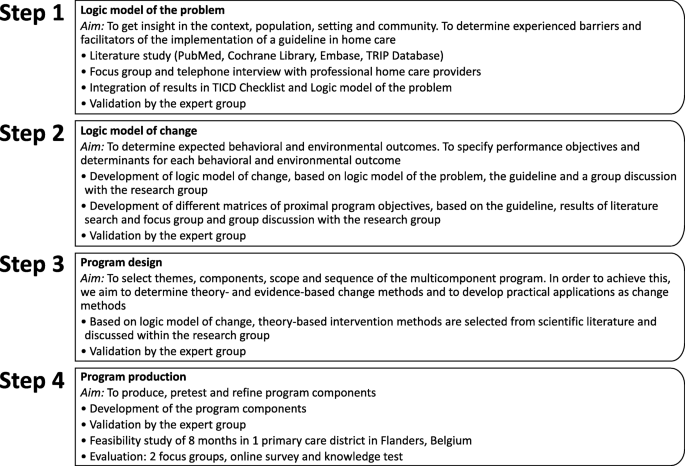

Intervention Mapping (IM) was used to develop a multicomponent program for supporting the implementation of the guideline for reducing the use of physical restraints in abode care [27]. IM provides guidance and tools to ensure that health promotion programs are based on empirical evidence and theories [27]. This mapping approach comprises six steps: (a) producing a logic model of the trouble, (b) developing a logic model of change, (c) programme design, (d) program production, (due east) plan implementation programme and (f) developing an evaluation program. This manuscript describes the operationalization of the first four steps of IM, the last two steps were non performed (Fig. 1) [27].

Overview performed steps Intervention Mapping [27]

IM is characterized by the involvement of different stakeholders during each step of the process [27]. An expert grouping of stakeholders was composed and met six times during the development process (June 2017 – May 2019). It included 11 participants: a GP, a self-employed registered nurse, a registered nurse of a dwelling house care nursing organization, two staff members of a dwelling care nursing system (organization of certified nursing assistants and registered nurses), a staff fellow member of a domicile care organization (arrangement of home health aides), a staff member of an system that represents family unit caregivers, an occupational therapist, a manager of a middle of expertise on dementia, a researcher and a senior academic staff member with expertise in behavioral change theories.

Step i: logic model of the problem

The first step of IM consists of a needs assessment. Information technology allows researchers to thoroughly analyze the trouble and create a logic model of the problem [27]. A literature search, complemented by a focus group interview with professional home care providers and i telephone interview with a GP, was conducted to get more insight into the context, population, and associated determinants. More information on the methodology of the literature search can be establish in boosted file 1. The focus group and the telephone interview aimed to obtain feedback from professional dwelling intendance providers on the identified barriers and facilitators of implementation from the literature search. Participants in the focus group interview were different from the adept group members; and were a GP, a self-employed physiotherapist, a deputy head nurse, a staff member of a home care nursing organization, a registered nurse and a certified nursing assistant. I boosted GP who could not attend, participated in a telephone interview. Ii researchers chastened the focus group (SV and KS). The interviews followed a topic guide and were recorded (additional file 2). The content of the written text was thematically analyzed, by identifying the primal themes (barriers and facilitators) that emerged from the data. The key themes and their underlying meaning were discussed within the research grouping.

The Integrated Checklist of Determinants of practise (TICD checklist) was used to structure the barriers and facilitators (determinants) based on the main findings of the literature search, focus group and phone interview [28].

Footstep two: logic model of change

Based on the results of the first step of IM and the content of the clinical do guideline, the research group adult the logic model of modify [15, 16]. This model specifies who and what needs to modify to properly manage physical restraint use in home care. In add-on, the plan outcomes and objectives were specified and the matrices of change objectives were developed. The developed matrices represent detailed change at individual, interpersonal and organizational level and as a consequence the immediate goals of the interventions of the multicomponent program [27]. Adjacent, the proposals of the logic model of change, the program outcomes and the matrices of change objectives were discussed with and evaluated by the expert group. Their feedback was discussed with the research grouping and integrated in the proposals. The final logic model of change, the program outcomes and the matrices of change were presented to the expert group, prior them granting approval. It concerned an iterative procedure, in which the research group collaborated with the experts.

Step three: programme design

The adjacent step was to select theory- and evidence-based methods, which could be effective in achieving the main objectives. Bartholomew et al. (2016) requite an overview of theory and bear witness-based methods that match certain determinants, which can be translated into practical applications [27]. The theory-based intervention methods and evidence-based intervention applications were selected from this overview [27, 29]. Based on the creativity, relevance, potential effectiveness and feasibility of the applied intervention applications, the expert group decided on a final choice of methods and applications.

Step four: producing and testing programme components

The fourth step of IM consists of producing the applied program components and testing and evaluating the program with the target population [27]. Practical components were developed by the inquiry group, with iterative feedback from the expert group. The multicomponent program was tested and evaluated in a feasibility report.

Feasibility study

The feasibility written report was performed from February 2018 until October 2018 in one of the 59 main intendance districts in Flanders (Belgium). This care commune contains 6 municipalities or care regions with a total of 103.225 inhabitants [30]. The Department of Welfare, Public Health and Family (Flanders) adult a website that provides an overview of professional domicile care providers and organizations in Flemish region and Brussels. Based on this website, the researchers made an overview of active professional home care providers and organizations in the selected care commune. In addition, the researchers asked a local multidisciplinary network (network of GPs and other professional home care providers) of the intendance commune to send an electronic mail invitation to their network members. All professional person habitation care providers (i.e. nurses, certified nursing assistants, GPs, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists) and organizations (i.e. dwelling nursing organizations, habitation intendance nursing organizations, home care organizations, senior and customs centers, organizations that provide assisted living) of the selected district were contacted by email and were asked to participate. All the interested professional home care providers and organizations received information and an informed consent form. At the start of the feasibility study an data session was organized, during which the guideline and multicomponent plan were presented. After this session, the professional domicile care providers and organizations were asked to give their informed consent for their participation. Professional home care providers who were actively engaged in the program (n = xv), received a training for becoming an ambassador for restraint-free home care and were stepwise exposed to all the components of the program through emails and a website. During the feasibility report, the newly trained ambassadors received ii peer coaching sessions and 1 call for process guidance.

Evaluation of the multicomponent program

A concurrent triangulation mixed methods design was used to evaluate the developed multicomponent program [31]. In this study, quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously, just analyzed separately. The different results were merged during estimation [31]. The evaluation consisted of a knowledge exam for the ambassadors and all professional home care providers from the participating organizations. The knowledge exam was not externally validated. However, the research group cautiously adult and evaluated the knowledge test based on the content of the guideline. This test had 0 as the minimum score and 31 as the maximum score. Furthermore, two focus group interviews and an online survey were held with the ambassadors to perform a process evaluation. They evaluated the different components of the multicomponent program and the feasibility of implementing a guideline of physical restraint utilize in home care. More information on the methodology of the knowledge exam, online survey and focus groups can be plant in additional file iii and the topic guide of the focus group interviews can be establish in boosted file 4.

The final results of the knowledge examination, the focus groups and survey were presented to the expert group and likewise to the ambassadors for restraint-free abode care. They were asked if the results were accurate and in line with their experiences (i.e. member checking).

Results

Pace 1: logic model of the problem

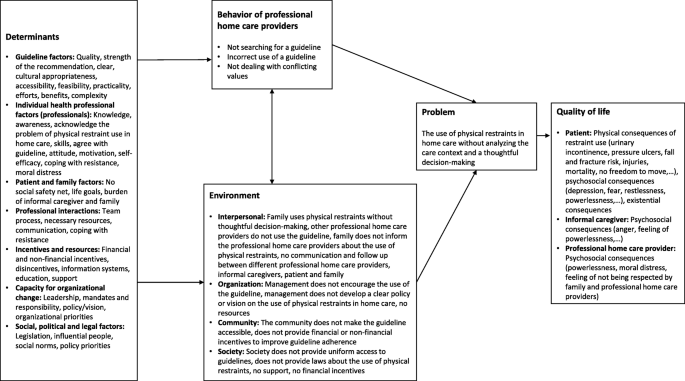

The results of the needs assessment can exist institute in the logic model of the problem (Fig. two). 'Quality of life' (QoL) is the ultimate outcome and formed the starting signal of the model. By placing the focus on QoL, the researchers were stimulated to think backwards through the logic model of the trouble to place the problem, the beliefs of professional home care providers, the environment and the determinants influencing the behavior and environs. The logic model of the problem helped the researchers to plan, implement and evaluate the program with the end in mind [27].

Logic model of the problem

Quality of life

Physical restraint use has an impact on QoL of the patient, the breezy caregiver and the professional home care providers. The patient can experience concrete (e.one thousand. urinary incontinence, pressure ulcers, falls, …), psychosocial (e.g. low, fright, …) and existential consequences [32, 33]. The use of restraints also comes with negative psychosocial consequences for the informal caregiver (e.one thousand. anger, powerlessness) and professional person dwelling house care providers (e.1000. frustration, moral distress) [1, 14].

Trouble

Due to demographic, epidemiological, social and cultural trends, in that location is a growing number of older persons living at home [34]. These older persons oft have chronic conditions, which are associated with restraint use. Consequently, professional dwelling house care providers are increasingly confronted with the apply of physical restraints [9, 33]. Findings from the needs assessment signal that currently concrete restraints are beingness used without analyzing the care context and thoughtful decision-making [ane, 2, 6].

Beliefs of professional person dwelling house care providers and environmental factors

Based on the findings of the literature search, the focus group interview and the skilful group meeting, different behavioral and environmental factors leading to a lack of thoughtful conclusion-making were identified. Non searching for a validated guideline, incorrect employ of the guideline and not dealing with conflicting values are behavioral factors at the level of home care providers. The environmental factors are classified into four levels; interpersonal, organization, community and society. The most important ecology factors at interpersonal level are the utilize of physical restraints past family unit without thoughtful decision-making and the lack of communication between home intendance providers, informal caregivers, family unit and patient. At the organization level, a lack of encouragement from management to utilize guidelines is a crucial factor. No access to guidelines for all professional person home care providers and the absence of financial and not-financial incentives to improve guideline adherence are the most commonly mentioned environmental factors on community and guild level.

Determinants

The most frequently-mentioned determinants are: the feasibility and practicality of the guideline (guideline factors); the knowledge, motivation and awareness of the professional home care providers (individual wellness professional person factors); the burden of informal caregivers and family, no social safety net and the alignment with the life goals of the older person (patient and family unit factors); communication between dwelling house care providers (professional interactions); fiscal and non-fiscal incentives (incentives and resources); leadership and organizational priorities (capacity for organizational modify); legislation and policy priorities (social, political and legal factors).

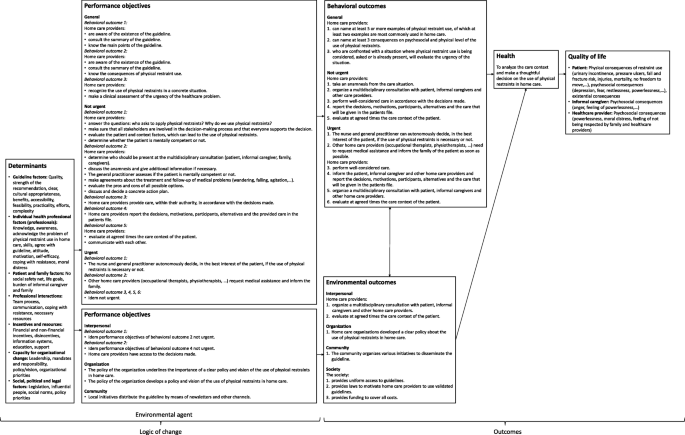

Pace 2: logic model of change

Logic model of change

Figure 3 shows the logic model of change. The overall wellness objective is that home care providers analyze the care context and brand a thoughtful decision on the apply of physical restraints in abode intendance. The logic model contains 14 behavioral alter outcomes. Additionally, the logic model has seven environmental outcomes at interpersonal, organisation, community and society level. The master behavioral outcomes focus on the awareness of the problem of concrete restraint apply, the knowledge of the guideline and the need for clear communication and collaboration between unlike care providers, patient, informal caregiver and family. The ecology outcomes mainly focus on a clear vision or policy regarding physical restraint use in home care organizations. In a higher place that, the dissemination and the accessibility of the guideline are taken into account. For each behavioral and environmental upshot dissimilar functioning objectives are formulated (Fig. 3).

Logic model of change

Matrices of modify objectives

For each behavioral and environmental outcome a matrix of change objectives was developed. The matrices were constructed by combining operation objectives with determinants and defining specific change objectives. These matrices course a concrete pathway for behavioral and environmental changes [27]. An case of a matrix of change objectives can be found in Table 1.

Footstep 3: program pattern

In the third footstep of IM, the research group and expert group of stakeholders selected theory- and evidence-based methods to influence the determinants identified in the logic model of alter and the different matrices of modify objectives. The principal theories behind the multicomponent program are the 'Social Cognitive Theory' and the 'Theory of Planned Behavior' [27, 35]. From the Social Cognitive Theory the researchers selected 'modeling', 'active learning' and 'guided practice' as bear witness-based methods to influence the identified determinants. With modeling nosotros aim to provide the professional home care providers an appropriate function-model, more than specifically an ambassador for restraint-complimentary home intendance. If the dwelling house intendance providers see and notice successful demonstration of behavior by a role model, they can reproduce the same behavior. The ambassadors receive a one-mean solar day training, where the trainers use the method 'active learning', learning based on goal-driven and activity-based experience. In addition, this training consists of 'guided exercise'. The ambassadors rehearse and echo behavior various times past means of role play. After the role play, peers hash out the behavior and give feedback. The main bear witness-based methods selected from the Theory of Planned Behavior are 'belief selection' and 'resistance to social pressure'. The strategy behind the method 'belief selection' is to use messages designed to strengthen positive behavior and weaken negative beliefs nearly physical restraint employ in home intendance. With this strategy in mind the researchers developed a flyer and a promo video. For the method 'resistance to social pressure', the ambassadors receive a training and peer coaching sessions to build skills for resistance to social pressure level. Table 2 gives an overview of all the selected theories, methods, implementation strategies and the practical components of the plan.

The developed multicomponent plan has three principal objectives: [one] to brand the guideline more accessible and to disseminate it, [2] to increase awareness and knowledge of the trouble of concrete restraint utilise in dwelling house intendance, and [iii] to work towards sustained implementation. Based on the theory- and bear witness-based methods, the research grouping and expert group of stakeholder selected and designed eight applied applications to operationalize those methods; i.eastward. a website, social media, promo video, flyer, summary of the guideline, physical restraints checklist, tutorials and ambassadors for restraint-free home intendance. More data on the dissimilar components of the program tin can be found in Fig. 4.

Different components of the multicomponent plan

Step four: producing and testing of programme components

In footstep 4 of IM the multicomponent program (Fig. 4) was tested for 8 months (February – Oct 2018) in one primary care commune in Flemish region, Belgium. In total, fifteen professional home care providers received a training for becoming an ambassador for restraint-free abode care. One professional person home care provider was a self-employed occupational therapist, the other ambassadors worked for diverse home care organizations, being: abode care nursing organizations (northward = 8) dwelling intendance organizations (organization of dwelling house health aides; due north = 3), a senior and community center (north = ane), an system that provides assisted living facilities (n = 1) and an adult day intendance middle (n = 1).

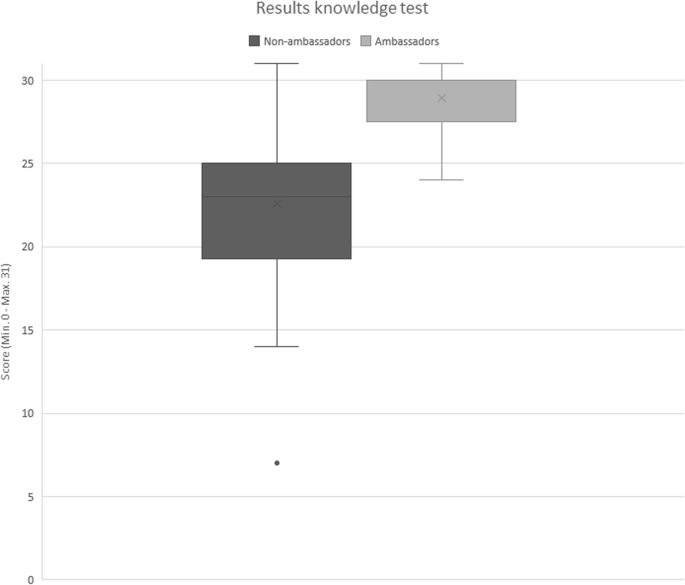

Knowledge

After 8 months of testing the multicomponent programme, a knowledge exam was completed by 73 dwelling care providers of the participating organizations, of which 13 were ambassadors and 60 were non-ambassadors (Table 3). The participants were mainly women (n = 71), with a mean historic period of 41.5 ± 10.6 years. The majority of the participants were certified nursing assistants (n = 23), dwelling house health aides (n = 22) and registered nurses (northward = 20).

The ambassadors scored noticeably higher on the knowledge examination (mean score = 28.9 ± 1.98) (than the not-ambassadors (mean score = 22.half-dozen ± 4.36) (Fig. 5). The non-ambassadors scored less on questions most the alternatives for concrete restraints and the legislative framework for physical restraint use in home care.

Results of the noesis exam for not-ambassadors (n = lx) and ambassadors (n = 13)

Procedure evaluation

A process evaluation was performed after 8 months of delivering the multicomponent program. Ten out of xv ambassadors participated in the online survey (results in additional file 5) and ix out of fifteen ambassadors participated in the focus groups. The results of the process evaluation are described in ii main topics: [1] the evaluation of the multicomponent program and [ii] the perceived barriers.

- 1.

Multicomponent programme

The results of the focus grouping interviews and the online survey show that the ambassadors acknowledged and appreciated the added value of various components of the program. Several components increased their knowledge and awareness of the problem of physical restraint utilise.

"The multicomponent plan is a valuable framework to support us to accomplish a physical restraint-gratuitous home care. Otherwise it wasn't feasible for usa."

"The multicomponent program was very important for awareness. Information technology was the first step to piece of work on a policy within our organisation".

The results of the process evaluation prove that non all components were evaluated equally positive. During the interpretation of the results of the survey and the focus group interviews, the researchers could place key components, valuable components and optional components. The key components are those components that are evaluated as the most crucial and useful components of the program. The valuable components are evaluated as useful and helpful, only study results point that they are not seen equally the near essential components of the multicomponent plan. The optional components are deemed valuable to particular professional home intendance providers, but for the ambassadors these components are less helpful and not highly-seasoned.

Key components of the multicomponent program

Based on the results of the online survey and focus group interviews, the ambassadors for restraint-free home care, the tutorials, the concrete restraint checklist and the flyer are defined by the researchers as the key components of the multicomponent program. According to the majority of the ambassadors, the training for becoming an ambassador restraint-gratuitous home care ensured that they could support their colleagues. All the ambassadors found that this training provided them with the necessary skills to give feedback to colleagues. Nine ambassadors stated that the training helped them to deal with resistance from colleagues. In addition, both the results of the online survey and the focus grouping interviews showed that peer coaching sessions and the telephone follow-up past the researcher continuously motivated and stimulated them to piece of work on a concrete restraint-free habitation intendance.

"The peer coaching sessions put the spark back in our work towards physical restraint-free dwelling intendance".

"In the phone follow-up, y'all ask questions "what are you doing, what is your progress?" And and so we start to think, how are we going to do information technology? ".

The two peer coaching sessions helped the majority of the ambassadors to empathize the legislation relevant to physical restraint utilise in Belgium and provided them with more insight into the different alternatives for restraint use. In the focus grouping interviews the ambassadors stipulated that they received data on the alternatives for physical restraint use, just in that location is however a demand to ascertain and provide alternatives.

"Legislation was very important and the alternatives were also of import."

"Can you develop something on the alternatives for physical restraints? Where tin can you get it? What is the price? Is it covered by the insurance company? What are useful tools?"

Participants indicated in the focus group interviews that they used the flyer to communicate with patients, families and caregivers, considering it was meaty, brief and concise.

"The flyer was also important. Because how do y'all go to the informal caregiver and talk over the use of physical restraints? The flyer is a useful tool."

Also the results of the focus group interview and online survey show that the concrete restraint checklist was perceived as a helpful tool, since it matched their daily working method and information technology supported the majority in documenting the intendance situation and the decision-making process. Other key components of the plan are the tutorials on the guideline and on the flowchart. In the focus group interviews the ambassadors evaluated the tutorials every bit useful and recognizable and information technology continuously motivated and stimulated them to piece of work on a physical restraint-free home care.

"The tutorials are very useful, the guideline is explained in an amusing style, and the cases appeal to the imagination."

In the online survey, 8 ambassadors found that the tutorial on the guideline raised awareness, supported and motivated them to use the guideline. All the ambassadors that have seen the tutorial on the flowchart believed that the tutorial supported domicile care providers in their daily practise, motivated them and antiseptic the use of the flowchart.

Valuable components of the multicomponent program

The results of the online survey and focus group interviews bear witness that the website and the promo video were seen every bit valuable components. All the ambassadors evaluated the website every bit logical and clear and it raised their awareness. Nine ambassadors indicated that the website supported them in their daily practise.

"I think the website is very important. We will also utilise information technology in the training of our professional home care providers."

The promo video was well evaluated by the majority of the ambassadors, it increased awareness and it motivated people to work on a concrete restraint-costless dwelling care. The ambassadors found that due to their didactics and experience, the professional person home care providers already knew the content covered by the promo video. Therefore, the promo video could exist more useful for the patient, family unit and informal caregivers.

"The promo video is for a broader audience, who do non know anything about it. It is important and convenient. If people already know the content, it is hard to keep their attention."

Optional components of the multicomponent program

The social media pages and the summary of the guideline are less well evaluated by the ambassadors. The majority of the ambassadors institute the social media pages (Facebook and Twitter) less helpful and not appealing. Half of the ambassadors did not visit the social media pages.

"Social media, I am non into social media. I take non been interested in social media and it does not appeal to me at all, maybe for young people."

The summary of the guideline aimed to support the professional person home care providers in the analysis of the care situation and the decision-making procedure. In the focus group interviews, the ambassadors indicated that the summary of the guideline was not useful and too complex. A minority of the ambassadors used the summary monthly.

"The flowchart, part of the summary of the guideline, is also circuitous to use especially for home health aides. We take made adaptations."

- two.

Perceived barriers to the implementation of the guideline

Several perceived barriers to the implementation of the guideline are identified from the focus grouping interviews. The ambassadors experienced that, in practice, the term 'concrete restraints' is being interpreted too narrow; only the most extreme and least adequate methods (e.g. ropes, belts) were taken into account. Due to the fact that 'physical restraints' has a negative connotation and abode care providers were not aware of the total significant of this term, it resulted in express recognition of the problem. And then, the narrow interpretation of 'physical restraints' by the ambassadors and other home care providers formed a barrier to fully exploit the added value of the multicomponent plan for the implementation of the guideline. The ambassadors constitute information technology important to think near a more suitable and compatible terminology and a articulate definition for physical restraints, so that defoliation could be avoided.

"Locking the door or room, people don't run into this equally physical restraints … Besides if yous forbid someone from going upstairs. Non everyone sees this as physical restraints."

The ambassadors found the fragmented approach in home intendance a challenge when trying to implement a guideline. They found it hard to involve and collaborate with dissimilar care providers such as self-employed nurses, GPs and physiotherapists. The ambassadors indicated that a common vision, full general agreements and uniform documents are of import to facilitate this collaboration.

"Nosotros desire to do it, only if the other care providers are not office of the story, we will remain in the physical restraints circle."

The legislation on physical restraint use was experienced every bit an important barrier to implement the guideline in dwelling care. In Belgium, simply doctors, nurses, certified nursing assistants (if they meet certain atmospheric condition such as working in a structured team and under straight supervision of a registered nurse) and informal caregivers (if they see certain weather condition such as training from a nurse or GP, informal caregiver document, …) can utilize concrete restraints [5, 10, 11]. The fact that an informal caregiver can be allowed to utilize physical restraints and that certain home care providers (e.1000. occupational therapists, dwelling health aides, and physiotherapists) cannot, influenced the self-epitome and self-confidence of these care providers. In improver, the ambassadors indicated that the current legislation is restrictive for some professional person home care providers.

"The legislation is very restrictive for abode intendance. If you apply it strictly, nosotros will requite the home wellness aides the feeling that they are unneeded."

"We have been very careful and have not explained the content of the guideline explicitly to the home wellness aides."

The ambassadors experienced a lack of time for facilitating the implementation as an important barrier. The entire process requires effort and time. The implementation process must be well thought out and prepared, before the bodily kickoff. With an implementation menstruation of just 8 months, all ambassadors perceived the feasibility report equally too short.

"It is such a short menstruum of time to realize it. And it takes fourth dimension to get more aware and to allow everything settle. And for an organization you have far besides little time to implement something. You solely have fourth dimension to create awareness."

Another challenge experienced by the ambassadors was the lack of involvement and support of their managers. The ambassadors plant it necessary that managers set priorities and develop a common vision and implementation program related to the use of physical restraints. Not all of the ambassadors had the organizational power to implement a guideline on concrete restraint use within their organization, which formed a bulwark for the implementation process.

"The management is not yet on lath. We need to involve them in order to implement it. Nosotros are now working on a vision or policy. That has been the bottleneck, to continue and have a complete concept. Everyone has to proceed, including managers. It must exist supported by the organization and the management."

Discussion

This study adult and evaluated a complex intervention to support the implementation of a guideline for reducing the use of concrete restraints in dwelling care. Modeling, active learning, guided practice, conventionalities selection and resistance to social pressure are the evidence-based methods used to select the 8 practical applications. The developed multicomponent program has three main objectives: to disseminate and make the guideline more attainable, to increase awareness and knowledge of the problem of physical restraint utilise and to work towards sustained implementation. This multicomponent program consists of eight practical components (website, social media, promo video, flyer, summary of the guideline, physical restraints checklist, tutorials and ambassador restraint-free home care). The guideline for reducing the use of concrete restraints in home care is non openly accessible and therefore information technology is not part of the adult multicomponent programme [fifteen, 16]. It could be assumed that this might form a barrier to using the guideline. For this reason, a summary of the guideline was developed. This summary contains the central points of the guideline and information technology also consists of the flowchart that guides professional home intendance providers through the decision-making process. In addition, the content of the guideline was extensively explained and discussed in the preparation to go an ambassador for restraint-free habitation care. The ambassadors for restraint-free habitation intendance received a free re-create of the guideline.

The results show that the multicomponent program is useful for implementing the guideline in domicile care. The ambassadors positively received, experienced and evaluated diverse components of the program. Components that were recognizable, compact, brief and curtailed, such as the concrete restraints checklist, tutorials and flyer, were best evaluated. The ambassadors indicated that due to the combination of the unlike components of the program their cognition, skills and awareness of the problem of physical restraint employ in home care had increased. Especially the tutorials and the training to get an ambassador restraint-free abode care, including peer coaching sessions and phone follow-upward, are considered essential for the program. The website and promo video are valuable, merely are not the essential components of the programme. In the focus group interviews the ambassadors did non put as much emphasis on the website and the promo video in comparison to the key components. Optional components of the multicomponent plan are the social media pages and the summary of the guideline. The ambassadors thought the social media pages were less appealing and saw the summary of the guideline, more in particular the flowchart, as too circuitous.

This study also highlights barriers to the implementation of the guideline. Start, the term 'physical restraints' is interpreted too narrowly. For this reason, information technology forms a barrier to fully exploiting the added value of the multicomponent program for the implementation of the guideline. Some ambassadors indicated that professional person home care providers were non aware of the wide definition of physical restraints as used in the guideline [15, xvi]. Only the extremes, such every bit belts and ropes, were taken into consideration, resulting in a limited recognition of the problem. From a literature search, Bleijlevens et al. (2016) identified 34 unlike definitions of concrete restraints [4]. The ambiguity about the term 'physical restraints' is well known [37, 38]. The results from our study further emphasize the need to search for a compatible term that describes the full scope. 2d, the fragmented approach in domicile care is besides a challenge. A lack of common vision, general agreements and uniform documents impedes the implementation process. A systematic review of reviews reveals that collaboration and good coordination betwixt the dissimilar stakeholders and organizations is important for implementation. Shared decision-making, non-hierarchical relationships, mutual respect, trust and open up communication are essential characteristics of good collaboration [xx]. Some other important barrier is the lack of involvement and support of managers. Literature as well underlines that support and commitment from managers who reaffirm the importance of change are of import facilitators for successful implementation in home care [20, 39,40,41,42,43]. In improver, the ambassadors felt that they did not take the organizational ability to conduct out this change project within their organisation. Earlier studies show that the absence of staff with the right competences or expertise impedes implementation [twenty, 39, 40, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. For this reason, the inquiry group formulated desirable competences (eastward.g. coaching skills, leadership). The participating organizations selected suitable candidates for becoming an ambassador for restraint-gratis habitation care. However, we did not verify if the candidates actually had these competences and organizational power to acquit out this change project. It is possible that not all of the selected candidates had the right competences (e.m. leadership, coaching skills) to facilitate the implementation of the guideline. Some other barrier is the lack of fourth dimension for facilitating the implementation of the guideline. Due to the relatively short implementation flow, the ambassadors felt they could only raise sensation of the problem of physical restraint utilize in domicile intendance. Indeed, literature shows that a lack of fourth dimension for planning and implementing new interventions or procedures is a bulwark. The organizational readiness (e.g. staff, preparation, strategic planning, resources) and the extent to which a new intervention fits in the electric current workflow influence the implementation process [20, 37, 42, 43]. Lastly, various ambassadors perceived the electric current legislation regarding the use of concrete restraints in dwelling house intendance as an important bulwark. Currently, the legislation regarding physical restraints use in Belgium is not articulate. In Belgium, non all professional care providers tin utilize physical restraints when needed. The problem is that the electric current legislation regarding concrete restraints is restrictive. For example, when a person is restrained and a professional home care provider, who is not allowed to apply restrains, is taking care of this person, the professional person home care provider needs to contact a doctor or a registered nurse to reapply the restrains when needed. However, in home care a doctor or a registered nurse is not always bachelor, which could mean that the use of restraints is either discontinued or that restraints are applied by persons who are neither authorized nor prepared for this. Therefore, the electric current legislation makes it difficult to perform integrated care and for this reason, it is complex to cooperate with different professional person dwelling care providers [five, 10, 11]. Literature reveals that the presence of an appropriate legislative framework is a powerful activator; while a lack of clarity about roles, responsibilities and tasks within the implementation procedure acts as important barrier. In addition, concerns nearly less autonomy, trust and independence impede the implementation of change [xx, 37].

This study uses Intervention Mapping in line with the widely used and cited United Kingdom Medical Research Quango (MRC) framework for developing and evaluating circuitous interventions. The MRC framework provides a useful general approach to systematically blueprint and evaluate complex interventions. The key elements of the evolution and evaluation process are: development, feasibility and piloting, evaluation and implementation [xviii]. In addition, this study uses Intervention mapping, which provides a systematic and logic process for intervention development, implementation and evaluation in accordance to the criteria of the MRC framework [27]. Yet, intervention mapping provides researchers more detailed and specific guidance during the development of the intervention [49,50,51]. Therefore, an important force of this report is the use of Intervention Mapping in the systematic development of the multicomponent program [27]. By using this mapping approach, we applied four perspectives during all steps of the development process. With the (a) participation perspective, we intended to involve the target group and plan implementers. (b) The multi-theory perspective stimulated us to arroyo real-life issues with multiple theories. (c) The systems perspective indicated that interventions need to be seen as role of a system, with interacting factors. (d) Finally, with the social and ecological perspective, we took the impact of the social and ecological atmospheric condition on behaviour into account. The developed multicomponent program includes clear objectives, methodologies and relates to behavioral change theories [27, 52]. Some other strength of this study is that nosotros performed a process evaluation of the multicomponent program with the intended program adopters. A process evaluation is an essential part of designing and testing a circuitous intervention, such as a multicomponent program for the implementation of a guideline [53]. The feasibility study is useful for getting a sense of how care providers perceived and evaluated the unlike components of the programme [xviii, 21]. In addition, the process evaluation gave us more insight in the contextual factors (e.g. perceived barriers and facilitators), the implementation process (east.m. the use of the different components of the plan) and the mechanisms of bear on (eastward.g. participants' responses to the unlike components) [53]. These results can exist used to optimize the multicomponent program.

Nonetheless, it is important to annotation the limitations of this written report. The first limitation is the express involvement of direction. A alter requires time, resources and sufficient back up. Therefore, the interest of this group is already crucial during the development phase and should be strengthened in future efforts. Another limitation is that patients, informal caregivers and cocky-employed dwelling house care providers are insufficiently represented in the development stage of the study. Diverse initiatives were taken to involve these groups; simply this proved to be difficult. A possible explanation for their absence, is that given the sensitivity of this topic and the negative connotation of the term 'concrete restraint utilize', no patients, informal caregivers or self-employed abode care providers were willing to participate. At that place are also some limitations of the feasibility study. Start, the knowledge test was charily constructed based on the content of the guideline and evaluated past the researchers of the inquiry grouping. All the same, the knowledge test was non externally validated, and therefore the results for this knowledge test need to be interpreted with some caution. 2nd, just two thirds of the ambassadors participated in the online survey (n = ten) and the focus groups (northward = 9). Not all of the trained ambassadors evaluated the multicomponent program. A possible reason for not evaluating the multicomponent plan can be the limited duration of the feasibility study (eight months). The ambassadors were still working towards increasing awareness. Not all the ambassadors had the time to apply the dissimilar components of the program. It can be assumed that we performed the evaluation besides early on in the procedure. For this reason it is important to interpret the results of the procedure evaluation with caution. The management is also comparatively involved in the feasibility study. This could explicate why the ambassadors did not experience support from the management of the organization. Lastly, we let the participating organizations select the suitable candidates for becoming an ambassador for restraint-gratis dwelling intendance. The findings of this study emphasize the necessity to carefully select the ambassadors based on strict competences (e.k. motivation, coaching skills, feel with change projects, leadership).

Prior to further implementation, futurity inquiry needs to focus on the fifth and sixth step of IM. An integral program for wider implementation needs to exist adult (footstep v of IM – Program implementation program). In addition, it is important to determine the effects of the multicomponent program on the attitudes, self-efficacy, knowledge and skills of the professional home care providers. Furthermore, nosotros demand to gain more insight into the implementation outcomes (achieve, dose, fidelity) and the effect of the multicomponent program on the utilize of the guideline for physical restraint use in abode care (e.thousand. cluster randomized controlled trial, hybrid designs) (step 6 of IM – Evaluation plan).

Conclusions

Nosotros tin conclude that the multicomponent programme shows promising results for implementing the guideline for reducing the use of restraints in home care. The multicomponent program is necessary, withal not fully sufficient to guide the full implementation of this guideline. Prior to farther implementation, research is nevertheless necessary and needs to focus on larger scale implementation and evaluation of the effect of the multicomponent programme. For future implementation it is important to involve all stakeholders from the beginning of the implementation process, use uniform terminology and a uniform definition for physical restraints, select competent ambassadors, clinch purchase-in of the direction and facilitate collaboration between different home intendance providers.

Availability of information and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- IM:

-

Intervention Mapping

- GP:

-

Full general Practitioner

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

References

-

Scheepmans K, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Paquay L, Van Gansbeke H, Boonen S, Milisen K. Restraint utilise in domicile care: A qualitative report from a nursing perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2014;fourteen(1):17.

-

Kurata South, Ojima T. Knowledge, perceptions, and experiences of family caregivers and home care providers of physical restraint use with home-dwelling elders: A cantankerous-sectional report in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:39.

-

Scheepmans K, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Paquay Fifty, Milisen K. Restraint apply in older adults in home care: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:122–36.

-

Bleijlevens MHC, Wagner LM, Capezuti Eastward, Hamers JPH. Physical restraints: consensus of a research definition using a modified Delphi technique. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2307–ten.

-

Belgielex. 10 mei 2015 - Gecoördineerde moisture betreffende de uitoefening van de gezondheidszorgberoepen. https://www.ejustice.just.fgov.exist/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?linguistic communication=nl&la=N&cn=2015051006&table_name=wet. Accessed 1 April 2019.

-

De veer AJ, Francke AL, Buijse R, Friele RD. The use of physical restraints in home intendance in the Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1881–6.

-

Hamers JPH, Bleijlevens MHC, Gulpers MJM, Verbeek H. Behind closed doors: involuntary treatment in Intendance of Persons with cognitive impairment at habitation in the Netherlands. JAGS. 2016;64(two):354–8.

-

Scheepmans Yard, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Paquay L, Van Gansbeke H, Milisen K. Restraint Employ in Older Adults Receiving Home Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1769–76.

-

Scheepmans One thousand, Milisen K, Vanbrabant K, Paquay L, Van Gansbeke H, Dierckx de Casterlé B. Factors associated with use of restraints on older adults with domicile care: A secondary analysis of a cross-sectional survey written report. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;89:39–45.

-

Belgielex. 12 januari 2006 - Koninklijk besluit tot vaststelling van de verpleegkundige activiteiten die de zorgkundigen mogen uitvoeren en de voorwaarden waaronder de zorgkundigen deze handelingen mogen stellen. http://www.ejustice.simply.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=Due north&cn=2006011246&table_name=wet. Accessed 18 April 2019.

-

Belgielex. 18 juni 1990 - Koninklijk besluit houdende vaststelling van de lijst van de technische verpleegkundige verstrekkingen en de lijst van de handelingen die door een arts aan beoefenaars van de verpleegkunde kunnen worden toevertrouwd, alsmede de wijze van uitvoering van die verstrekkingen en handelingen en de kwalificatievereisten waaraan de beoefenaars van de verpleegkunde moeten voldoen. http://www.ejustice.only.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?linguistic communication=nl&la=Northward&table_name=moisture&cn=1990061837. Accessed 18 Apr 2019.

-

Goethals S, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C. Nurses' descision-making in cases of physical restraint: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(half dozen):1198–210.

-

Haut A, Kolbe Northward, Strupeit S, Mayer H, Meyer G. Attitudes of relatives of nursing home residents toward concrete restraints. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(iv):448–56.

-

Gastmans C, Milisen K. Utilise of concrete restraint in nursing homes: clinical-ethical considerations. J Med Ideals. 2006;32(three):148–52.

-

Scheepmans M, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Paquay Fifty, Van Gansbeke H, Milisen One thousand. Streven naar een fixatiearme thuiszorg: Praktijkrichtlijn. 1st ed. Leuven: Acco; 2016.

-

Scheepmans K, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Paquay L, Van Gansbeke H, Milisen K. Reducing physical restraints by older adults in home care: evolution of an show-based guideline. BMC Geriatr. 2020;twenty(1):169.

-

CEBAM. Belgisch Centrum voor Evidence Based Medicine. https://world wide web.cebam.be/. Accessed 3 October 2020.

-

Grol R, Wensing 1000, Eccles M, Davis D. Improving patient care - the implementation of modify in health care. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley; 2013.

-

Mickan Due south, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of "leakage" in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:670–9.

-

Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic 1000, Treweek S, Eldridge S, et al. Achieving change in primary care — causes of the show to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci. 2016;11:40.

-

Richards D, Hallberg I. Complex interventions in health - an overview of inquiry methods. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2015.

-

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie South, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating circuitous interventions : the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;l(five):587–92.

-

Gulpers MJM, Bleijlevens MHC, Ambergen T, Capezuti E, Van Rossum E, Hamers JPH. Belt restraint reduction in nursing homes: furnishings of a multicomponent intervention programme. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2029–36.

-

Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Gerlach A, Haut A, Haastert B, Möhler R, et al. Issue of a guideline-based multicomponent intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2177–84.

-

Kong EH, Song East, Evans LK. Effects of a multicomponent restraint reduction program for Korean nursing habitation staff. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(3):325–35.

-

Möhler R, Richter T, Köpke Southward, Meyer G. Interventions for preventing and reducing the use of physical restraints in long-term geriatric care - a Cochrane review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Interv. 2011;2:3070–81.

-

Bartholomew LK, Kok One thousand, Ruiter RA, Fernandez ME, Markham CM. Planning wellness promotion programs: an intervention mapping arroyo. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2016. p. 704.

-

Flottorp SA, Oxman Advertizing, Krause J, Musila NR, Wensing M, Godycki-cwirko M, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35.

-

Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GY, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour alter methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(three):297–312.

-

Verschueren K. Omgevingsanalyse op niveau van de eerstelijnszone. Thema: zorg voor welzijn en zorg voor gezondheid. Eerstelijnszone Demerland. https://www.eerstelijnszone.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Omgevingsanalyse%20op%20niveau%20van%20ELZ%20Demerland_4.pdf. Accessed 1 October 2020.

-

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. One thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017. p. 520.

-

Evans D, Wood J, Lambert 50. Patient injury and physical restraint devices: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(3):274–82.

-

Hofmann H, Hahn S. Characteristics of nursing home residents and physical restraint: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23:3012–24.

-

Hoeck South, François Chiliad, Geerts J, Van der Heyden J, Vandewoude Thousand, Van Hal G. Health-care and habitation-care utilization among fragile elderly persons in Belgium. Eur J Pub Wellness. 2012;22(5):671–7.

-

Glanz K, Bk R, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health pedagogy - theory, research and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 590.

-

Belgielex. 10 OKTOBER 2008. - Besluit van de Vlaamse Regering tot regeling van de opleiding tot polyvalent verzorgende en de bijkomende opleidingsmodule tot zorgkundige. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&table_name=moisture&cn=2008101036. Accessed 24 December 2019.

-

Kong E, Choi H, Evans LK. Staff perceptions of barriers to concrete restraint-reduction in long-term care: a meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:49–threescore.

-

Hamers JPH, Meyer Thousand, Köpke S, Lindenmann R, Groven R, Huizing AR. Attitudes of Dutch, German and Swiss nursing staff towards physical restraint apply in nursing home residents, a cross-sectional report. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):248–55.

-

Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Shakibazadeh E, Rashidian A, Hajimiri 1000, Glenton C, Noyes J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of doc-nurse substitution strategies in primary care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;four:CD010412.

-

Sunaert P, Bastiaens H, Feyen Fifty, Snauwaert B, Nobels F, Wens J, et al. Implementation of a program for type ii diabetes based on the Chronic Care Model in a hospital-centered health intendance system: "the Belgian experience". BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2009;9:152.

-

Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for booze misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2010;33(3):412–21.

-

Kadu MK, Stolee P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in master care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;xvi:12.

-

Mckenna H, Ashton Southward, Keeney South. Barriers to evidence based practice in primary care: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(4):369–78.

-

Batchelor F, Hwang K, Haralambous B, Fearn M, Mackel P, Nolte L, et al. Facilitators and barriers to advance care planning implementation in Australian aged care settings: a systematic review and thematic analysis. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(three):173–81.

-

Martinez C, Bacigalupe One thousand, Cortada JM, Grandes One thousand, Sanchez A, Pombo H, et al. The implementation of health promotion in primary and community intendance: a qualitative analysis of the ' Prescribe Vida Saludable ' strategy. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:23.

-

Sopcak N, Aguilar C, O'Brien MA, Nykiforuk C, Aubrey-bassler K, Cullen R, et al. Implementation of the Better 2 plan: a qualitative report exploring barriers and facilitators of a novel style to improve chronic disease prevention and screening in chief care. Implement Sci. 2016;eleven:158.

-

Addington D, Kyle T, Desai S, Wang J. Facilitators and barriers to implementing quality measurement in primary mental health care - systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(12):1322–31.

-

Rubio-valera Thou, Pons-vigués M, Martinez-Andrés M, Moreno-Peral P, Berenguera A, Fernandez A. Barriers and Facilitators for the Implementation of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion Activities in Primary Care: A Synthesis through Meta-Ethnography. PLoS One. 2014;9:2.

-

French SD, Green SE, O'Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour alter interventions to implement evidence into exercise: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(38):i–8.

-

Hurley DA, Murphy LC, Hayes D, Hall AM, Toomey Eastward, McDonough SM, et al. Using intervention mapping to develop a theory-driven, group-based complex intervention to support self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain (SOLAS). Implement Sci. 2016;11:56.

-

O'Cathain A, Croot Fifty, Sworn K, Duncan E, Rousseau North, Turner K, et al. Taxonomy of approaches to developing interventions to improve health: a systematic methods overview. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;v:1–27.

-

Kok G, Bartholomew LK, Bundle GS, Gottlieb NH, Fern E. Finding theory- and evidence-based alternatives to fear appeals: intervention mapping. Int J Psychol. 2014;49(ii):98–107.

-

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Procedure evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:1–seven.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would like to thank the expert grouping of stakeholders, the ambassadors and the participating organizations.

Funding

The Flemish Authorities, Department of Welfare, Public Health & Family funded this study. The funding agency had no part in the blueprint of the report, writing the manuscript and the collection, assay, or interpretation of data.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

SV, KS, KM, TvA, BD: study design and evolution of the multicomponent plan. SV, KS: data collection and data assay. SV, KS, KM, TvA, EV, JF, BD: drafting the manuscript. KS, KM, TvA, BD: supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Commission of Leuven University Hospitals, on 17 August 2017 (One thousand-2017 08 877). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Koen Milisen is senior editor for BMC Geriatrics and Bernadette Dierckx de Casterlé is associate editor for BMC Geriatrics.

Additional information

Publisher'southward Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, every bit long as you give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and signal if changes were made. The images or other third party fabric in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If fabric is not included in the article'south Creative Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Vandervelde, S., Scheepmans, 1000., Milisen, K. et al. Reducing the use of concrete restraints in home care: evolution and feasibility testing of a multicomponent programme to support the implementation of a guideline. BMC Geriatr 21, 77 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01946-v

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01946-5

Keywords

- Dwelling intendance services

- Primary Wellness Care

- Implementation science

- Do Guidelines as Topic

- Restraint, physical

- Aged

andrzejewskiafroping.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-020-01946-5

0 Response to "Write a Program That Reads Data From Restratings"

Post a Comment